In its opening scenes, the immortal line, “In a galaxy far, far away”, teased the idea of new, unseen worlds in what we would come to know as the Star Wars universe.

From the cold desert moon Jedha and the forest moon Endor, to the rebel headquarters on the jungle moon Yavin 4, moons have played an important part of the Star Wars landscape.

When the first film was released in 1977 these fantastical places really did seem ‘far, far, away’ and as the latest instalment of the Disney franchise is about to hit cinemas, it’s likely that astrophysicists (the ones who happen to be into Star Wars) have debated what the reality of those types of planets being able to sustain life is.

But without access to the Millennium Falcon, the Star Wars moons are outside our reach and we’re left with our own galaxy, which aren’t as far, far away – so could we really inhabit planets or moons away from earth?

While it might sound as unfathomable as Jabba the Hutt on a treadmill, in fact, many of the worlds depicted in Star Wars could exist in our universe – particularly if we colonised the older moons which have become tidally locked to the planet they orbit, and their orbits more circular. Dynamically young moons, despite looking habitable on paper with the right atmosphere and temperature, would likely have significant tides from the much larger planets they orbit; this would cause daily volcanic activity, even before discussing what might happen to any oceans on these moons

In our own galaxy, Kepler-16b is a Saturn sized gas giant orbiting two stars with a combined mass comparable to the sun at a distance close enough for liquid water to exist, known as the habitable zone. However, the planet itself is not habitable as it is too large, but it does have the potential to support a moon; recent research suggests that an earth-sized moon could orbit this binary planet and be habitable, proving that moons orbiting planets just like Tatooine can exist.

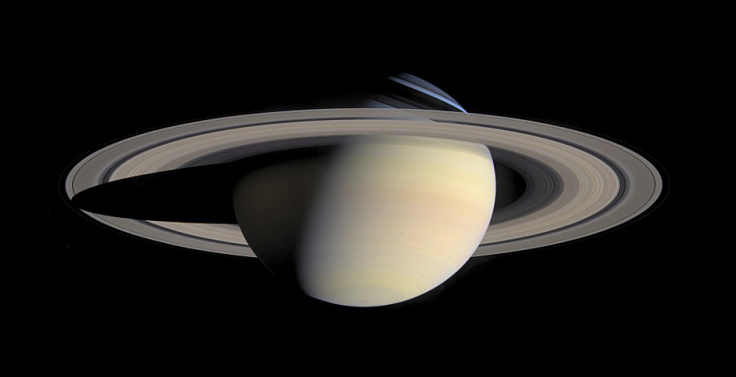

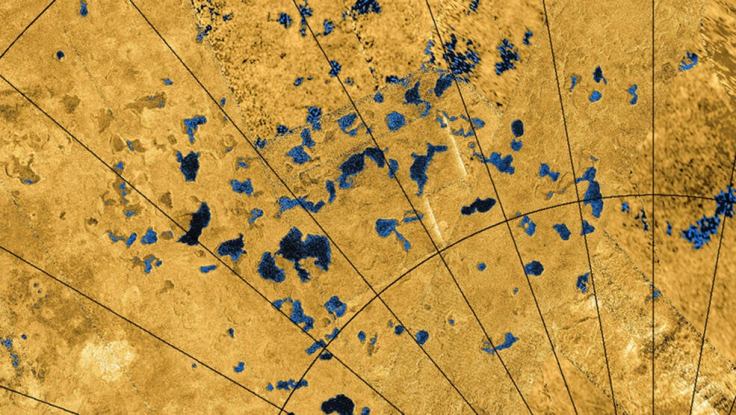

Two relatively nearby moons that are strong candidates that could support life are Enceladus and Europa which are moons orbiting Saturn and Jupiter respectively.

Both of these moons are a long way from the Sun and have frozen surfaces which are hostile to life, but the close proximity to their host planets can cause some internal heating, which is thought to maintain the liquid water oceans located under the deep-frozen surface. Enceladus, Saturn’s icy moon can be seen to have large cracks in its surface spewing out water ice from its liquid ocean beneath, powered, at least in part, by the large tides from Saturn.

Now, though, evidence is beginning to show that exomoons – a natural satellite that orbits a planet just like Earth’s own moon, but outside of our solar system – are viable targets for the search for life.

The more work that is done on exomoons and their link to those depicted in sci-fi suggests that it is difficult to form earth-like moons around large planets close enough to their stars that they have earth-like surface properties. For example, a recent study showed that Hot Jupiter’s – large gas giants that are close to their stars – cannot form earth-sized exomoons as they move inwards to their current location close to the star.

A more likely scenario for a planet to have a sufficiently large moon that would be habitable, like those in Star Wars, is if they were smaller planets that came to close to the planet and were captured. We do know this can happen as Neptune captured a dwarf planet with an atmosphere which is now known as Triton.

Triton is in fact larger than Pluto, yet is classed as moon due to being captured by the gravitational field of Neptune. The difference here is that Neptune is a long way from the strong gravitational forces of the Sun. A Hot Jupiter would have to compete against a much closer star in order to capture a moon, making it harder to have an earth-like moon close enough to its star that we could live on the surface.

Despite the exhaustive efforts to detect exomoons none have been confirmed – recently, I was investigating the whether gaps formed in a large ring system around the exoplanet J1407b could have been formed by an unseen exomoon. I ran simulations to see if this would confirm the theory, but it actually showed the opposite.

Hopefully as we do more investigations into our vast universe, these elusive exomoons will become more common, similar to what has happened to the explosion in exoplanet discoveries in the last few decades, which now stands at just over 4,000 confirmed exoplanets.

This is an exciting possibility, and would be a genuine potential for living outside of our own Solar System, but right now we’re not at the level seen in Star Wars.

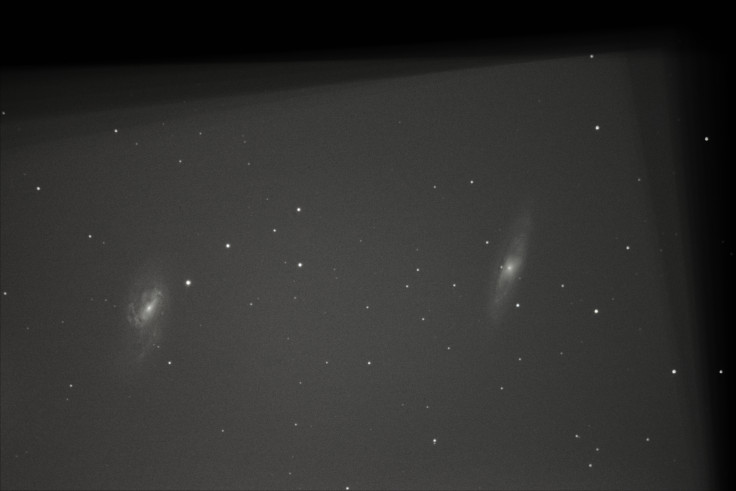

M104: The Sombrero Galaxy. An almost edge on lenticular galaxy which is inbetween a spiral and elliptical galaxy. These types of galaxies have very little star formation and are populated by older stars.

M104: The Sombrero Galaxy. An almost edge on lenticular galaxy which is inbetween a spiral and elliptical galaxy. These types of galaxies have very little star formation and are populated by older stars.